Crested Butte . . . Love at First Sight Excerpt

CHAPTER 16 – The Shovel Patrol

Fresh from college and working the cash register at my mother’s Village Store, I waited each day for the ski patrolmen to come in for soda pops and lunch snacks. Some were casual acquaintances or had wives or girlfriends; others were fair game for flirting. Watching the skiing saviors cruising by in tight ski pants, the backs of their jackets adorned with medical crosses, I thought them handsome, eligible, and oh so glamorous.

Comparing notes with former patrollers John Burns and Mike Burns (same last name, but no relation), I discovered that John entered the occupation with a similar impression, albeit from a different angle.

“I asked Crested Butte ski patrol leader Don Bachman for a patrol job in 1966,” said John. “I thought it would be so cool. A season pass, a jacket with a red cross on the back, skiing whenever I wanted. Don hired me, and I went to work the next day—with a shovel!”

A shovel was not standard issue equipment for a ski patrol position, but John soon discovered its purpose.

John and Mike both loved skiing, but admitted that they could not conform to the high standards set by ski school director Robel Straubhaar.

“And you didn’t get paid unless you taught lessons,” Mike pointed out, adding with a grin, “They had the glamour job. We had the fun job.”

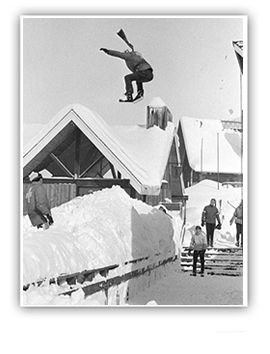

Not very fun for John and Mike was skiing awkwardly downhill carrying their two long ski poles with large, woven leather baskets while balancing a big snow shovel over their shoulders. If snow was sparse, they would shovel it from the sides onto the trails to cover rocks lurking to trip up unsuspecting skiers. Then they would pack the upper slopes using their shovels, boots, and skis. They also served as the maintenance crew at the base area, shoveling roofs and keeping wooden decks and steps clear of ice and snow—using muscle, not the modern snow blower.

“We made $360 a month for six days a week and if it snowed on your day off, you came up anyway,” recalled John.

Many ski area workers and the Burns boys, as we called them, attended Western State College in Gunnison part-time, scheduling classes around their paying jobs. John tended bar in 1968 at Tony’s Tavern owned by Don Bachman and his then wife Adele.

Don recalled via e-mail that at least two patrollers were always stationed in the top patrol cabin adjacent to the gondola terminal. In the 1960s, with only a few hundred skiers per day, if that, accidents were rare and when one did occur, the first on the scene could report it to a lift operator or find the nearest of six, military surplus, E-8 crank phones. Each phone was located in a box marked with a number and a red cross and attached to a tree or gondola tower. Then, just like Radar O’Reilly in the “M* A* S* H” movie, the caller had to vigorously crank the handle until someone picked up on the other end.

“The phones rang everywhere including the base area office,” said John. “Whoever answered would ask you which number box you were at, and to look uphill and describe where the accident was. That gave the top patroller an idea of where to find it. If the phones didn’t work, someone had to climb every gondola tower, which is where the phone line was strung, to find out where the problem was and fix it.”

The Outer Limits, the original moniker of today’s Extreme Limits, were not open to the public then. However, the ski patrollers did avalanche control work on Keystone Ridge, Monument, and Horseshoe above the maintained runs. Today they are part of the skiable Extreme Limits. At the time, Crested Butte had the second most dangerous in-bounds avalanche zones in the state.

Rudy Somrak, known as young Shammy, was a Crested Butte native and the Forest Service snow ranger in charge of explosives. His assistant was his Uncle Johnny Somrak, a retired coal miner. In the 1960s, according to John Burns, a red, padlocked, plywood box full of dynamite was kept in the trees on the upper part of the mountain.

“Anyone with a claw hammer could have gotten in there,” said John. “Shammy kept the caps in his office and brought them to the top patrol room where we would help insert them into the one-pound charges. Johnny Somrak would supervise attaching and cutting the fuses. Johnny had worked with dynamite in the mines, and he told us we were safe if we had an eighteen-inch fuse. You can bet we measured those fuses exactly.”

The eighteen inches gave the patrollers ninety seconds to pitch the bomb and cover their ears and asses, turning away before the charge exploded and kicked loose the unstable snow, sending it plunging downhill below them.

A grinning Mike took up the story. “We carried the charges in our backpack to where they needed to be thrown. If they go off, you’re vaporized. There’d be nothing left but your boots.”

John recalled falling on the T-bar slope with a pack full of charges. Some rolled out. The bombs were unstable nitroglycerin dynamite, a fact very much at the forefront of John’s mind while he scrambled to find them all in the deep snow.

His partner suggested, “Just poke around with your pole,” an action that could have set them off.

“Another time,” said John, “we were throwing charges near Monument. I pulled the igniter and tossed it and the fuse wrapped around the gondola cable. Don Bachman and I stared at each other for long seconds before it finally dropped. God, can you imagine blowing up the gondola?”

“It’s a wonder that we didn’t all die!” said Mike, laughing at the memories.